Episode Transcript

[00:00:00] Speaker A: Imagine a justice system built on rigorous evidence, not gut instincts or educated guesses about what works and what doesn't.

More people could access the civil justice they deserve.

The criminal justice system could be smaller, more effective and more humane.

The Access to Justice Lab here at Harvard Law School is producing that needed evidence. And this podcast is about the challenge of transforming law into an evidence based field.

I'm your host, Jim Griner, and this is Proof Over Precedent.

[00:00:34] Speaker B: Hello and welcome to the Proof Over Precedent podcast. We're back once again with Renee Dancer of the Access to Justice Lab. Hello, Renee.

[00:00:42] Speaker C: Hi, Michelle. Good to see you again.

[00:00:44] Speaker B: And you.

And what we always like to do is to find out fun facts about people. We're getting to know Renee really well, so I hope you have some more interesting fun facts that you're willing to share about yourself.

[00:00:56] Speaker C: I did prepare another.

So I am learning Spanish using duolingo and I am on a nearly 600 day streak. Oh, yes.

[00:01:08] Speaker B: I've never heard anybody having that long of a streak.

[00:01:11] Speaker C: I started learning doing it because I was going to be traveling to Mexico and I wanted to, you know, try to learn the language and engage in conversation and I just never stop. Duolingo is really good about forcing. You just keep going. I don't know if you've ever used.

[00:01:32] Speaker B: It, but there's pressure.

[00:01:34] Speaker C: Yes, they have figured out, like, how to make people do things.

It's a combination of encouragement and shame.

[00:01:42] Speaker B: So the rewards really win you over too, right?

[00:01:44] Speaker C: Yes, exactly.

[00:01:46] Speaker B: Knowing that there's a competitive streak out there.

I hear you. So did you get to use your Spanish in Mexico?

[00:01:52] Speaker C: Yeah, yeah. And since, since that particular time I've gone back to Mexico and gone to Spain. So I've been able to use my Spanish and each time it's a little bit better. I'm not fluent. In fact, I did have an interesting conversation with a woman in Spain and she said to me in Spanish, your Spanish is not that good, but you're trying.

And I understood, which was good to know.

[00:02:21] Speaker B: Right, but that counts for something.

[00:02:22] Speaker C: She's right, though. It's a fair assessment.

[00:02:26] Speaker B: Wow, that's bold.

Well, speaking of other languages, this particular next project is about another part of the world, in Africa. Can you tell us a little bit about the Africa project?

[00:02:39] Speaker C: Yes, absolutely. So we're working with the International Legal foundation, which is a US based organization, but their focus is looking at or implementing programs that put together indigent defense, specifically with the goal of providing early access to quality defense counsel for indigent individuals who are arrested and entrapped in the justice system in their country.

We were working in Nairobi, Kenya and in Tunis and Sus Tunisia, so two African countries, but very different in many respects.

[00:03:29] Speaker B: So this study is a little different than our other studies in many ways. A lot of times we like to talk about our successes and pat ourselves on the back about how well our RCTs are going. This one at this point has been discontinued, which is a different thing to talk about here. So we are talking about a failure and lessons learned.

But, you know, let's first go into it talking about what our hopes were of what we would learn. So if you can just tell us about how far the project got to and how that, how it looked.

[00:04:01] Speaker C: Yeah, so this project got far. So it's discontinued because we received a stop work order from the federal government who was the primary funder of the. About both the evaluation as well as the implementation of the intervention. So the work that, that the ilf, the International Legal foundation was doing, but we had, I mean, we were up and running. It was amazing and really exciting work to think about. Kind of all of the challenges of working across countries, but like so far away. So far away. So we had launched in Kenya, in Nairobi. We had launched in September of last year.

We received our stop work order in mid January of this year like most people did or most projects did. And we had enrolled almost 600 people. We were on pace, the pace that we had said we would get to. We were on pace and we had, I mean, the intervention was being delivered. The individuals who are supposed to be receiving the early intervention of Quality Counsel were receiving it. We had managed a fully remote process for overseeing the study because we at the Access to Justice Lab are overseeing the mechanism of the study in order to give it fidelity to the pro to the evaluation itself. So we had a fully remote or a fully online mechanism to do the consent with the facilitation of the paralegals in the office in Kenya.

They were also facilitating the fully online and remote baseline survey operation. And we had programmed a website to do the randomization piece. And so they were able to easily access that we were collaborating online. So I would wake up every morning, they would have completed their day because they're eight hours ahead of us. And I would see all the people that they had successfully enrolled in the study. And also if there were, you know, if there was an issue, I would see that later than I would like. But yeah, it was so exciting. And we, like I said, we had nearly 600 people. We had a precisely 559 people enrolled at the point in time where we received the stop work order.

[00:06:39] Speaker B: That sounds like it ramped up pretty quickly. Is that faster than some of the projects usually take?

[00:06:46] Speaker C: This project actually did go fairly quickly. It was a quick start to finish. So we had the inquiry from the ILF about helping them with the evaluation. They had a really quick turnaround on the requests for proposals from the federal government, where we had to talk about what the intent of the evaluation would be and how much that would cost and what our methodology and plan was.

Then we heard about that, about that award in September of 2023. And I told you, we launched in September of 2024. So we spent that year's time getting everyone in Kenya, like, ready to go, which meant standing up in office because they didn't have indigent defense before this. So this was a fully new integration of indigent defense in a location that did not have it already. Now, in Tunisia, the ILF had established offices. This project had hoped to expand the catchment area where those offices could work so into new jurisdictions. But in Kenya, there was no ILF office. There was no indigent defense at all. So it was not only getting the study ready to go, which is also its own kind of parallel animal, but it was getting the office up and running. So that was finding space and hiring people. I mean, all these, like, little things that are actually big things. Right, of course. So.

[00:08:31] Speaker B: So actually, as this is, I believe, the Access to Justice Lab's first global project.

[00:08:37] Speaker C: Is that, right? Yeah. So I would assume first one that we've launched.

[00:08:41] Speaker B: First one we've launched. Okay. So I would assume that there are some challenges that come with being, you know, global program and different. Different rules, different laws.

And it sounds like, obviously you already ran into one challenge in Kenya. There. Are there any other challenges you came across just working globally?

[00:08:58] Speaker C: Yeah. Well, in Tunisia, Kenya, the primary language spoken is English. They do. Their national languages are both Swahili and English. And so everything is in English and Swahili. But you can.

All of the records are in English. All of the proceedings are in English. They do translate into Swahili because most actual native speakers are speaking Swahili, especially going through the court system.

But in Tunisia, that is not the case in Tunisia, English is not on the list of national languages. Right.

So. And it's also a different Alphabet.

So those are two practical barriers that made things challenging in Tunisia.

We had translators on every meeting, for example, and we translated all of our materials into multiple different languages. So we translated them into Standard Arabic, into Tunisian Arabic, and then also into French.

I learned a lot about Arabic dialects doing this project. There are a lot of them and they're all very different. And so it was really for me just like a cultural exploration in addition to.

And hopefully I can express my humility because I was not aware of a lot of things. And it was really, it was worthwhile for me in that respect too.

[00:10:31] Speaker B: But.

[00:10:34] Speaker C: We had lots of data partners, different data partners to work with and that involved a lot more higher level bureaucracy than I think we certainly deal with bureaucracy, especially with data collection in the US but it felt at a higher level there.

And it was all very political. Right, too. So because all of these offices are also political offices, just the same as in the US So in Kenya that was, I think, a barrier we're familiar with. But it felt like it was at a different level. In Tunisia, it was even harder because it's just a different type of government there too. And so navigating that was oftentimes something that we couldn't even be in control of or it was difficult to convince or not convince, but push along the project because we really weren't in control of that.

And the ILF's control was also limited because it really required ministers of various departments to push that through.

Okay, so.

[00:11:56] Speaker B: So there were some challenges. It sounds like you. And you went over to Africa yourself, is that right?

[00:12:00] Speaker C: Yeah, I went to Nairobi twice.

Maybe three times. No, I think just two.

Maybe three, but I think two.

And the first time it was I went with folks from the ilf. Like I said, that's also a US based organization. So we all went together and those meetings were mostly about giving those offices that I just talked about an overview of the project and the evaluation. We met with folks from the embassy at the like the U.S. embassy.

And that was more of a lay the groundwork and then also go to court. Like I wanted to see how the court operates and like where would we actually operationalize the delivery of this intervention as well as the like invitation to the study, like how would that work? And so I wanted to see those things so that we could adequately prepare and recognize some of the barriers. So we were super fortunate in Nairobi that it is very kind of tech enabled. So we were able to have some of these remote management processes among the team, which included folks in Nairobi as well as folks here in Tunisia. That's not the case.

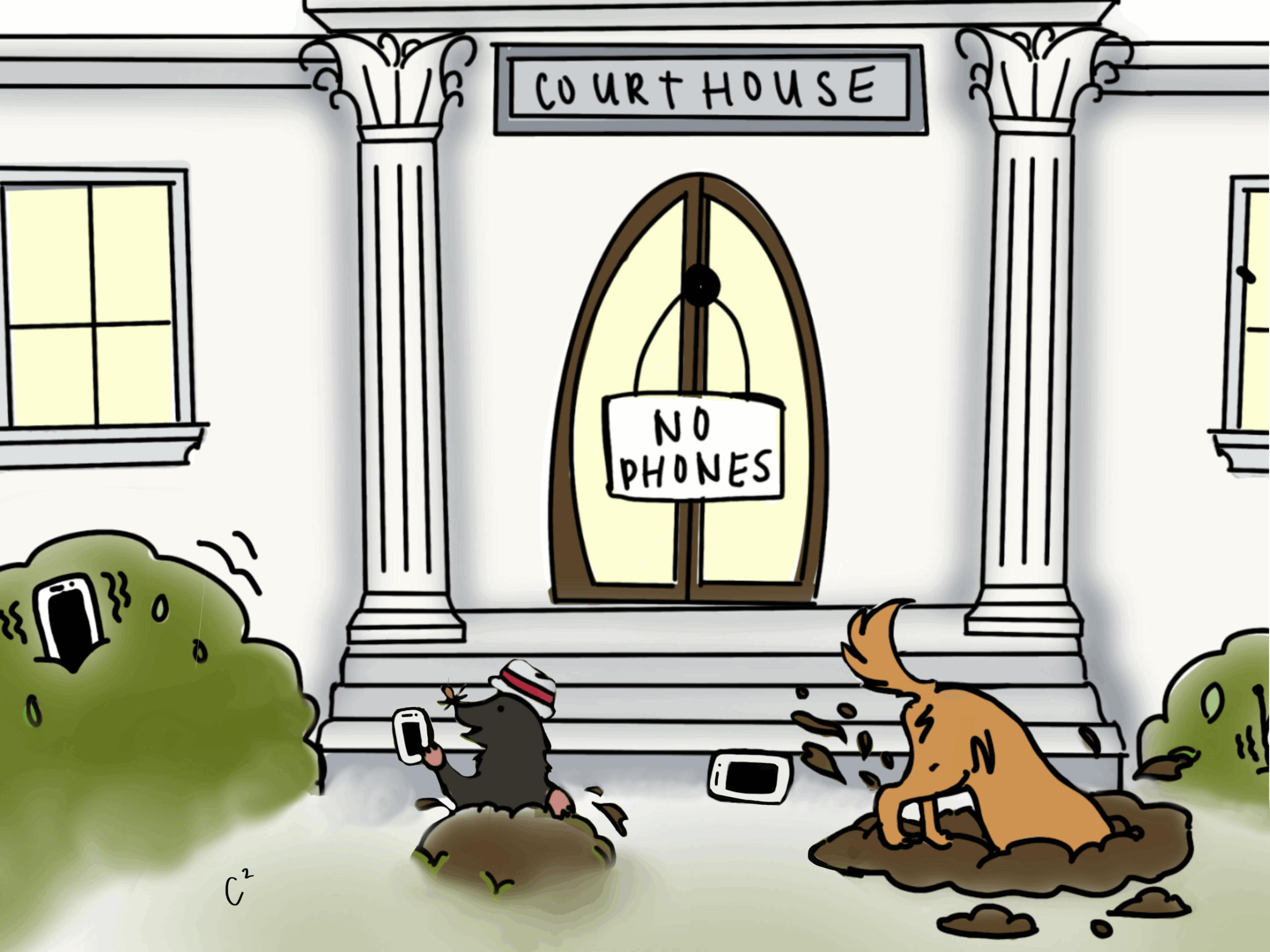

They're not allowed to. Even the attorneys are not allowed to bring computers into the police station. No Phones.

So having these remote processes were much more difficult there and perhaps impractical.

[00:13:41] Speaker B: Wow, that would be a challenge.

This is possibly not to be kept on the podcast, but CAFA as a separate study.

I'll just sit as a question. This might get deleted, but you've completed a different study that addressed council at first appearance.

Is that something we can even look at as a comparison for similarities and differences?

[00:14:06] Speaker C: So it is in the sense that the programs with the International Legal foundation are attempting to provide early access to counsel for the council at first appearance study. That is a US based study. And it's really isolating the experience of having counsel at that bail hearing. And where there is the right to counsel that we all are so familiar with in criminal cases actually doesn't extend to that bail hearing.

So there are lots of folks in the US who don't have counsel then and they're not appointed counsel at that point. So they're arguing for their initial release or release conditions without the benefit of counsel, who might be maybe more familiar with the law. And also the just general practice in the Kenya and Tunisia context, we aren't just isolating that instance.

We're also looking at the effect of having early access to counsel, but also kind of what does the quality.

The ILF's theory of change really is that it's not just about having a lawyer present. It is about having a quality, quality counsel present and handling your case through to its end. So they are the same and different in like a nuanced way that maybe actually is not important. Right.

[00:15:49] Speaker B: Okay, we'll move on from that one then.

So, you know, it sounds like you didn't necessarily get too far down the road. You got the enrolled participants, but the study did not yet begin, is that right?

[00:16:03] Speaker C: Well, the study began because we enrolled participants. So we launched the study in September of 2024.

We received the stop work order, which meant we had to stop. We couldn't. We can't even do analysis. Like we're not. There's nothing more we can do on this evaluation, even though we have that 559 people enrolled. And many of them, I mean, all of them took a baseline survey.

We were just about to begin collecting some administrative records. I mean, like we had that process in place and so we don't actually even have the administrative records that we would have analyzed. But we were hoping to enroll for one year. So this is a shorter study, I think, than most of our studies. And so we were, you know, a little, we were a little under halfway.

[00:17:00] Speaker A: Okay.

[00:17:01] Speaker B: And so the timeline overall for, you know, at the. At the point when you expected to have results from the study, where were you anticipating that landing?

[00:17:11] Speaker C: So we.

This, like I said, is a shorter study than most. We were scheduled to enroll for one year, following folks for six months. So that's a really short period of time.

And then we left three months for data analysis and evalu and report writing, which is, like, really woefully short. This was a timeline dictated by the grant itself.

Okay. And there was.

There often is not a lot of wiggle room in awards from the federal government, but there. There definitely wasn't in this one either.

[00:17:47] Speaker B: Okay, so as far as where it stands now, are we re abandoning it, or is it on pause until hopeful funding comes down the road?

What do you think?

[00:17:59] Speaker C: We, I think, are on pause. I think that's a great way to characterize that. So we do have a funding request out, and we're actively looking for funding to both restart the intervention and restart the evaluation. So we've kept all the mechanisms for all of the things we put in place for the evaluation with the hopes that we could restart pretty shortly after receiving additional funding or new funding.

I think part of the challenge here is that the funding was not only for the evaluation, but also to start up the intervention. And so that means that the folks that were hired, for example, come from that funding. And so it's disappointing to have the evaluation end, but it's actually the least of the issues related with the kind of abrupt stopping of the funding. There were people's lives who abruptly stopped as well. So we might have to reconstitute that team.

May not be fair to those individuals, but also would, you know, may mean we have to start from square one. So we'll see. But I think we're hopeful to restart it. We think it's a great study. We think it's exciting.

It's like, was working like the study itself was in the field. And that's an amazing accomplishment, I think.

And it was just a really interesting piece of work.

[00:19:40] Speaker B: So that's an interesting takeaway that we were able to get it this far, if you've sort of touched on this. But are there any other big learning points you want to highlight as far as things we can take away from this?

[00:20:00] Speaker C: I think, you know, I think the big point that I want to, like, leave us with is that we want to restart the study. Right. We're actively looking for funding.

We are ready to go, and it was a huge accomplishment for us to start up the funding or, excuse me, to start up the study. But more than that, just like observing what, Observing what? Was observing the court operations in Kenya and to see how the community kind of rallied around doing this evaluation. And the court was really wanted to figure out how to make change for the folks that were processing through this system without the benefit of counsel or without the fair benefit of counsel was really great to see, but also hard to work through.

So we were enrolling people while they were in holding cells. We were able to remove them from the holding cell into a private meeting room. But just to kind of how a different system is working was really eye opening for me. Sure.

[00:21:17] Speaker B: Anything else you'd like to discuss about this project?

[00:21:20] Speaker C: No, thank you. So. Oh, actually, yes, we did collaborate. I think it's really important to mention we did collaborate with researchers on the ground too. So in both countries we had local researchers helping us. So in Kenya, we worked with a gentleman named Lenson Nijoku. And in Tunisia we'll be working with an organization called Global Assistance Consulting.

And so that was really important for the success of the project because they were able to be actively at the courthouse when we needed them to be there. Or in Lenson's case, he was administering surveys in incarceration facilities when study participants were still there. He was actively following up with families when we were not able to reach them so that they could continue doing surveys. So it was a real key component to the evaluation, and so we would never have any success without that. And in addition to kind of the participant communication, many of these records are on paper. They're not online, or they're not in any data repository other than a physical file.

So we also.

It was important to partner with local researchers for the, you know, just honoring the cultural component of the evaluation, but also for practical reasons of helping us to gather administrative records. And then we had kind of the second piece of that, which was coding all of those.

[00:22:56] Speaker B: I'm kind of going a couple steps backwards, but you were talking about the human component. This might be an offline question, but you talked about kind of the human component that was affected by the lack of funding at the start of this year.

As far as lessons learned, do we take anything away from this in terms of recognizing where we get our funding from? Or is that something that we are going to be looking at closer going forward? Or is this a, you know, this is.

[00:23:29] Speaker C: Well, I think that it was a surprise, maybe. I mean, it's hard to say that. I don't think that many people feel like this is a surprise anymore.

But we thought we had a often grants from the federal government were.

They were very selective, but they were also, you could rely on them.

And so we were.

This was not like outside of the confines of the contract that you enter into. This was certainly within the termination provisions of the contract, at least on its face.

There might be other things that I don't know about, and so maybe that shouldn't be a part of the podcast.

[00:24:27] Speaker B: But.

[00:24:30] Speaker C: We were surprised, I think even after we knew the results, even after we saw kind of the future coming down, I think I was still a little surprised that this project in particular was selected.

[00:24:46] Speaker B: Okay.

All right. Well, I asked you already about other things to discuss.

You're all set?

[00:24:52] Speaker C: All set.

[00:24:54] Speaker B: All right. Well, thank you, Renee, for joining us today. I appreciate you getting into some of the successes and unfortunately, the pauses we'll say with this Africa project.

[00:25:04] Speaker C: Yes, thank you.

[00:25:06] Speaker A: Proof Over Precedent is a production of the Access to Justice Lab at Harvard Law School.

Views expressed in student podcasts are not necessarily those of the A J Lab.

Thanks for listening. If we piqued your interest, please subscribe wherever you get your podcasts. Even better, leave us a rating or share an episode with a friend or on social media.

Here's a sneak preview of what we'll bring you next week.

[00:25:32] Speaker C: So under the current dangerousness standard for commitment, access to care is compromised for non dangerous individuals who need but are refusing treatment.

So this is interesting and really sad when you think about the fact that it forces relatives to watch their loved ones go through like, progressive stages of psychiatric decompensation before they're allowed to get them any help.

Image by Felicia Quan, J.D. candidate, Harvard Law School

Image by Felicia Quan, J.D. candidate, Harvard Law School